Combat PTSD, Dissociation, and Your Criminal Charges

A Defense Primer

Criminal trial defenses related to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are overlooked or dismissed too easily in today’s justice system. 2.7 million Americans have served in Iraq and Afghanistan.1 Post Traumatic Stress Disorder has been assessed in approximately 20% of those Veterans, according to the Veterans Administration (VA).2 Another 19% have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI). A RAND Corporation study found only 50% of these veterans seek treatment for PTSD. 3 Half of those receive “minimally adequate” treatment.4

Roughly 15 – 30% of Veterans suffering from PTSD reported episodes of depersonalization and derealization, otherwise known as “dissociation.”5

Look no further than the ribbons that adorn the chests of Marines, Soldiers, and Sailors in today’s military courtrooms to appreciate just how many of these combat veterans find themselves in the criminal justice system. Careers are shattered; freedom is taken, in one fell swoop. Dishonorable or Bad Conduct discharges leave the troubled veterans unlikely to even obtain VA medical care for their war wounds, let alone a decent job.

In ways that are being understood and quantified more each year, the tangible, physiological effects of PTSD and TBI can render combat veterans incapable of acting with criminal intent during the course of exceptional triggered reactions. Uncharacteristic misconduct predictably results. Severe symptoms can give rise to defenses to crimes ranging from first-degree murder to larceny to drug use. Yet, these casualties of a volunteer force are discarded as criminals in the system. In the most fundamental sense of the word, that is not “justice.”

In this article, I am going to explain what we know about PTSD and Dissociation; How it physically changes the brain; the Perfect Storm that typically precedes a veteran’s incident or arrest; and what a trial involving this type of defense might entail.

An Appropriately Uncommon Defense

Before I launch into the details of these defenses, I want to emphasize that “lack of mental responsibility,” “diminished capacity,” or “not guilty by reason of insanity” defenses are rare- for good reason. Individuals suffering from severe PTSD do not continually exist in an altered state of consciousness. PTSD symptoms including depression, anxiety, survivor’s guilt, avoidance, re-experiencing, and alcohol abuse, while a daily prison for many of our combat vets, generally do not alone serve to negate their criminal responsibility. A person may have chronic, severe, combat-related PTSD and also be equally as “guilty” of intentionally engaging in criminal behavior.

The criminal episodes described in this article usually happen within treatment and diagnosis gaps, with the incidents typically serving as the catalyst to the proper approach in therapy. Thus, while the residue of combat trauma will always remain, treatments like Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), exposure treatment, reprocessing, service dogs, holistic-type therapies, and medication management equip PTSD-sufferers with the ability to cope and thrive in their daily lives. Veterans with PTSD properly identified and treated are not irreversibly “broken,” imminent risks, or “ticking time bombs” in the least.

However, the physiological changes described herein are well-settled and real. They result in more criminal incidents than the Department of Defense would like to admit. These veterans deserve an informed defense in these instances.

It should also be remembered that a “lack of mental responsibility” trial acquittal in the military does not necessarily mean that everyone goes home at the end. As I discuss below, even if a complete “lack of mental responsibility” defense is successful, the defendant will have to prove in a post-trial hearing that his release would not create a substantial risk of danger to another. If he is unable to “prove” this, then a wide range of options for care or committal for care exist.

“Thousands of other Marines and soldiers are serving honorably with PTSD”

It would be untrue to say chronic PTSD sufferers are categorically not responsible for crimes. It is similarly absurd to discount the mental responsibility defense of one combat vet because other vets “with PTSD” have not experienced the same physiological effects. Two different people may suffer from PTSD generally, but demonstrate vastly different symptoms and physical effects. The spectrums of PTSD and TBI are broad, ranging from mild to severe, with various subtypes. A constellation of complications, triggers, and factors combine to physically (yes, physically) alter and overwhelm different minds in vastly different ways. Some veterans experience chemical and physiological changes that others simply do not. Personal weakness has nothing to do with it.

Officials unwaveringly give lip service to the need to care for our combat veterans when they return home. We all lament PTSD as a casualty of war. However, when sometimes-ugly outcomes predictably arise, the support melts away, and the servicemember is pursued as zealously as any other perceived “criminal.” This demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of PTSD and TBI. The judicial system has not been immune from this misunderstanding.

In two different military trials wherein my clients and I presented the defenses I discuss here, the Commanders and prosecutors repeatedly exclaimed that PTSD was “no excuse,” because thousands of other Marines serve honorably with PTSD. By the end of this article, the fallacy of such logic will be clear.

One Marine’s Story

A few years ago, in 2011, I teamed up with Marine Major Tim Kuhn to represent a highly-decorated Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant at his General Court-Martial on Camp Pendleton, CA. He was a father, husband, son, and leader with an impeccable career. He was battling chronic PTSD and TBI. Now, he was facing life in prison without the possibility of parole.

We could find no one who knew of a military case where the effects of PTSD and TBI had even been considered as a full defense to these types of crimes in a court-martial. However, we knew our client. We knew his past. We knew who he was before, during, and after each of his 5 combat deployments between 2004-2011. We learned who he was before his TBI. And his second TBI. And his third.

We gleaned third-party accounts of the battlefield horrors he endured; the mind-bending risks he took as an Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) technician; and the day his rifle was jammed, only to learn the muzzle was clogged with chunks of his obliterated dear friend after an IED blast. We read the accounts of his Bronze Star with a combat “V,” his Navy Achievement Medal with a combat “V,” his Purple Heart, and his several other personal awards with combat distinguishing devices. We knew his family. We knew his parents. We knew his friends. His troops. He never made excuses, and certainly would not miss deploying with his fellow Marines in 2011 because of “mental issues.” He was going to rub dirt on the wounds and “stay in the fight.”

We saw what his doctors said about his spotty treatment history and his state of mind. He had been tossed a 7-drug cocktail of antidepressants and sleep meds while still in Afghanistan earlier in 2011. When he came home, it was medication roulette and difficulty in refills. We looked at the weeks, days, hours, and moments leading up to his allegations. There was no denying the facts of the violent incidents. However, we talked to witnesses and victims. And we learned very clearly: in the moments of the offenses, it was not him. He was not himself. His consciousness of self had disintegrated.

In the days leading to the incident, he was embroiled in a profound mental struggle that most of us could not comprehend. Short individualized dissociative episodes were interjecting themselves with more frequency. He struggled to hold himself together, not fully understanding what was going on around him. His brain had been chemically and hormonally regressing. And the longer it went inadequately treated, recognized, and contained, the more severe, chronic, and dire the effects and symptoms became. He was in quicksand.

He did not commit those crimes. This was a hijack.

This was not a case for jail time. His PTSD, TBI, and combat record was not some “mitigation material” to knock a couple months off the sentence. It was the cause of the crime.

After over a year of litigation, the jury acquitted this Marine of all charges. After a post-trial hearing (discussed at the end of this article), this Marine retired honorably and returned to his family.

After that case, I had the honor of successfully defending another combat veteran in 2013 with a similar PTSD-related defense, discussed below. In both cases, justice was absolutely served. When the Institution’s proverbial back is turned on suffering combat veterans in certain meritorious cases, these veterans deserve defense attorneys, medical professionals, and judges who understand PTSD/TBI, the viability of such defenses under the law, and are not desensitized to the invisible wars of our returning vets.

Our Evolving Understanding of PTSD

As long as rough men have engaged in combat, the depravity of war has poisoned the mind. The poet Homer described the post-combat trauma symptoms of Achilles in the Illiad6 and Odysseus’ mental transformations after 10 years of war in Odyssey.

Civil War veterans with paranoia, guilt, insomnia, or manic episodes were said to have “soldier’s heart” or “acute mania.” Interestingly, these soldiers were often dismissed as having “character flaws” or even physical conditions from ruck sacks’ strings being drawn too tightly.7

The same symptoms were labeled “shell shock” from exposure to exploding artillery shells in World War I. The Times in London observed in a 1915 article: “The soldier, having passed into this state of lessened control, becomes a prey to his primitive instincts… He is cut off from his normal self and the associations that go to make up that self. Like a carriage which has lost its driver he is liable to all manner of accidents…”8 Keep this 100 year-old observation in mind as I explain dissociation, “amygdala hijack,” and mental responsibility. Nevertheless, “shell shocked” soldiers were often discarded as weak and relegated to asylums.

And most-infamously, after the Vietnam War, with thousands of American sons exhibiting symptoms, a “stress response syndrome” was diagnosed. But in yet another way our Vietnam vets were spat upon, PTSD was labeled a temporary transitory condition- an “adjustment disorder.” Thus, vets symptomatic for more than 6 months were considered to have a pre-existing condition or behavioral problem, not related to Vietnam service, and were denied VA coverage. Little did we understand just how chronic severe PTSD can be.

In 1980, PTSD was finally termed and recognized by American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III as an “anxiety disorder.”

With our modern abilities to MEDEVAC and treat those physically wounded in battle, 90% of those wounded in OEF/OIF have survived. That’s much higher than in past conflicts. With the relative increase in wounded warriors actually returning home, we see a greater intensity and pervasiveness of combat stress and its effects in our daily lives.

The Diagnostic Criteria of Chronic, Severe PTSD

But even today, we are still in the relatively early stages of PTSD understanding, learning more each year. Just less than two years ago, the DSM-V reclassified PTSD from an Anxiety Disorder to Trauma and Stress-Related Disorder.

Severe forms of PTSD act to invade the rational brain. It is a complex, and multi-faceted external attack upon the central nervous system. Chronic, severe combat-related PTSD re-wires the brain. It’s not an anger management problem. PTSD subtypes can be of such severity to physiologically overwhelm a person’s ability to function. The brain physically changes in quantifiable, observable ways we never previously could understand. We are only just recently developing and implementing imaging tools to identify and treat.

While the ultimate severity depends upon many factors, all Post-Traumatic stress involves:

- Exposure to extreme trauma “beyond the pale of normal human experience.” This trauma involves feelings of terror, the threat of death. It is horror beyond the tolerable or controllable limits existing in the mind. Often, in this event itself, the first “dissociative reaction” happens.

- Secondly, the mind continues to re-experience that trauma. Whether still in theater or stateside, images from the trauma consistently invade the mind, ranging from vivid daydreams to nightmares to “flashbacks,” hallucinations, and dissociation.

Triggers. Triggers are just those subconscious (or sometimes conscious) sensory stimulations that “remind” the brain of the feelings of hopelessness, terror, and distress that were carefully recorded in the original trauma. Triggers often cause re-experiencing. Triggers do not always have to be battlefield-related. They can come from sensations that grab the right parts of the emotional memory, which could happen in a crowd at the mall, while driving a car, watching fireworks, or when cornered in an argument, for example. When these sensory triggers happen the body re-experiences that same toxic hormonal process all over again.

3. Thirdly, with PTSD comes the Avoidance of stimuli associated with the original trauma. Both consciously and subconsciously, the brain, having memorized all associated stimuli, seeks to avoid the damage previously suffered.

Negative alterations in mood and behavior progress in severity unless properly mitigated. Cycles of “chronic over-arousal” and “anxious apprehension” leaves the individual consistently unable to concentrate, hypervigilant, and fearful. The individual will be unable to sleep or relax, be easily startled, increasingly mentally-aroused with paranoia, guilt, aggression, or panic. People often have a negative sense of self and recurring self-blame. When chronic insomnia finally gives way to sleep, that sleep is plagued by nightmares. In avoiding triggering places, people, and memories, the individual will be seen as “zoning out” or detaching from emotional engagement. Short and long-term memory is diminished. Joy gives way to numbness. Deep and genuine feelings, even when with children who are loved, are muted.

Even while on deployment, the actual chemical composition of the warrior’s brain can show signs of change. Life may lose value, and the individual may take risks recklessly. On the other hand, fellow Marines or soldiers may observe hypervigilance in the sense that everything is perceived as a critical threat. Not that the PTSD-sufferer is necessarily jumpy or cowardly. But rather, for instance, the person will seem obsessive-compulsive. Misplaced or malfunctioning gear becomes life threatening. He obsessively plans and stews over detail to an unhealthy degree. The irrational self-blame for failures, injury, or death starts here.

Severe, chronic forms of PTSD can affect consciousness. Some manifestations of PTSD override cognitive function. In other words, the sufferer becomes a prisoner to a mind that has been hijacked. The ability to form “criminal intent” is diminished while experiencing severe symptoms of certain subtypes. Chronic, severe PTSD “with Dissociative Symptoms” is one such subtype.

The Dissociative Subtype

In yet another brand-new addition, the DSM-V specifically recognized “with dissociative symptoms” as a subtype of PTSD, an understanding of which is critical for any attorney defending combat veterans with PTSD.

Dissociation is a “disruption of identity.”9 Quite simply an individual experiencing a severe dissociative reaction cannot comprehend their current setting or environment. The individual grossly misconstrues what is occurring and what threats exist. They do not understand the nature, extent, or wrongfulness of their actions in these moments.

Criterion B3 in the DSM-V states, “Dissociative reactions, in their most extreme form can result in “complete loss of awareness of present surroundings.”10 The DSM-V describes symptoms of “depersonalization” and “derealization” as indicators of this subtype.

“Survival mode.” “Autopilot.” “Out of body experience.” No matter the name, it is the “disintegration” of the present (sense of) self. Revealed in severe forms of chronic PTSD, dissociative reactions are not nervous breakdowns or anger-induced “blind rage.” A dissociative episode is not akin to an “alcohol blackout” where memory is walled off because of booze. No, in a dissociative episode, consciousness is walled off.

Dissociation is a forceful intrusion upon the rational mind. A hijack. Thoughts or emotions come out of nowhere, and action seemingly initiated by a force other than oneself.11 Individuals become passengers in their own body. Fragmented memory can be recorded, but it is akin to brief glimpses outside the window of a dark room.

While in the throes of dissociation, the mind reverts to the original traumatic combat stress, with all attendant sensations, terror, and emotions. The body is a passenger as the mind reverts to “fight, freeze or flight” mode. Even if the triggering events culminate at home or a familiar place, the mind reacts as if life is threatened, as it was in the original trauma. And what does a combat trained veteran do in that instance? He reacts with aggression, seeking to search and destroy any threat the altered mind perceives. Military combat training instills instant reaction, instant obedience, automatic orientation, and swift action. This mental reaction explains some of the violent crimes that can result from severe dissociative reactions.

“Lucid Intervals” And Interaction with Surroundings. Since dissociation is not a rage outburst where high activity persists until the anger subsides, a dissociative episode can look more bizarre, confused, and fragmented in nature. “Lucid intervals” may be observed by witnesses during prolonged dissociative reactions. The individual seems to snap back into reality or interact normally with those around them, maybe even asking questions about what is going on, only to lose control again to this dissociative survival mode.

As I discuss in more detail below, the circuits of the brain are disregulated, modulating between rationally-controlled inhibition and emotional “activation.” Thus, in this modulation, witnesses may see the individual interacting coherently with the environment.

This is very important to understand. In the legal system, prosecutors, commanders, or a veteran’s own defense attorney may be under the impression that, unless a defendant was making battlefield-related exclamations in a zombie-like state, the actions were knowing and intentional. That’s not necessarily true. A dissociating Vietnam vet does not always think that the scene of the incident is a jungle. The scene of the incident does not have to “resemble” the desert, jungle, or setting of the original combat stress to be a “legitimate” dissociative episode. That’s not how this works.

Dissociation is not always the proverbial “flashback.” The key to a dissociative episode is that the mind isn’t comprehending the nature of one’s actions within the environment. The person could be interacting with the present environment while on “autopilot.” They may very well treat a shoe like a shoe, a door like a door, or a water faucet like a water faucet.

For instance, a sleepwalker is able to walk down stairs, open a refrigerator, and eat a ham sandwich, all without any cognitive or conscious appreciation of those objects or their actions. The dissociating combat veteran’s experience is, in many ways, similar.

Actions in this state may be against the law. They may be violent. However, by definition, if one is in a dissociative state at the time, then they were unable to comprehend the “wrongfulness” and “nature” of their actions. In this regard, they are “not guilty” of the crime. Certainly, it’s rare. But with the rate of severe, chronic, combat-related PTSD being the highest it has ever been for the American veteran, it happens. And it happens more than we are identifying in our court system.

How Trauma Physically Affects the Brain

To understand the Legal Defenses surrounding Dissociative Reactions is to understand the Brain Before, During, and After Extreme Traumatic Exposure.

In basic terms, your Central Nervous System relies upon two systems: the “Inhibition Circuit” and the “Activation Circuit.” In the healthy human adult brain, complex wiring/“white matter,” robust regions, and groups of nuclei work to produce behavior appropriate to the given circumstances. This incredibly and intricately wired system makes us so uniquely human.

Understanding how this system works is essential to understanding how the PTSD brain loses the ability to cognitively function in a dissociative state. Our Central Nervous System is based on neurons. Under trauma, neurons die and the intricate system loses balance. Receptors that previously caught synapses and sent them through transmitters are “disregulated.” The result can be extreme behavior.

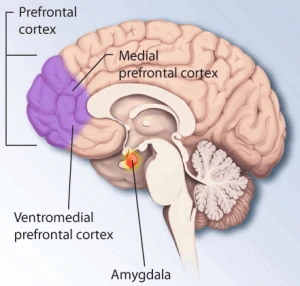

The Amygdala Hijack

The Amygdala is the catalyst of the brains “raw emotion,” as opposed to, say, the rational or thinking part of the brain. The Amygdala sends information that triggers anxiety, fear, or a “rush.” It arouses, for example, adrenaline, aggression, emotional intensity, and weakened self-control.

With a very powerful “emotional memory,” the amygdala memorizes every painful or frightening event the brain has ever experienced. When the amygdala is stimulated by a new trauma or stressor that it matches to a previous “fight or flight”/life-or-death scenario in its memory rolodex, it activates areas of the hypothalamus, adrenal cortex, and the “sympathetic” nervous system. Hormones and neurotransmitters like norepinephrine, dopamine, glucocorticoids, and adrenaline are then released.

One such hormone produced in the hypothalamus is the Corticotropin Releasing Factor (CRF). During stress, CRF release causes pure panic, fear, loss of appetite, rage, and depression. If the amygdala were to be likened to a rider whipping horses into a frenzy, then CRF would be the whip. The more intense the stress, the higher the CRF level. The higher the CRF level, the more norepinephrine and dopamine run wild. At higher levels, the brain is hijacked. The brain is running on pure emotion and instinct, potentially to the point of unconscious behavior.

The controlled rush of this activated circuit can prove valuable to warriors in combat, athletes, bystanders reacting to an emergency, etc. With release of endorphins, the body feels little pain in the moment. Focus is intense, and actions are swift. But amygdala hijack may also bring irrational behavior, tunnel vision, panic, and blind aggression.

The Hippocampus- Reining in the Amygdala

By contrast, a healthy Inhibition Circuit serves to rein in the amygdala, contextualizing events for the brain to process rationally. The prefrontal cortex and hippocampus also use recorded memory and strongly-held beliefs to rationalize and intervene before the amygdala can dominate with pure emotion.

The Hippocampus contextualizes experiences, saying, “This is not life or death. Everything’s ok. We’ve seen this before.” It’s your control center. In the sense of “Houston, we have a problem,” it’s Houston. Just as the Activation Circuit activates hormones and neurotransmitters, the “Inhibition Circuit” releases serotonin to rein in the norepinephrine and dopamine. Serotonin increases senses of well-being, control, and self-tolerance. In cases of chronic, severe PTSD, drugs (described below) are often prescribed to simulate and increase serotonin levels necessary for regulation.

Thus, in the ordinary traumatic scenario more mundane to the human experience (a minor vehicle accident, argument with a spouse, a grade school fistfight, intense sports participation, etc), the Rational brain is able to process the traumatic stimuli, put it into context, and prevent an irrational amygdala hijack. Since it is also important to have an appropriately active amygdala in even these more mundane traumatic scenarios, this integrated system requires a fine balance.

Cell Death Caused by Extreme Combat Stressors

Combat exposes the brain to traumatic information it has never before experienced or imagined. Firefights where life could end at any second. Close quarter, personal urban combat. Triple-stacked IED blasts that rip through a patrol. Ambushes. Sniper fire. The sensations involved in taking the life of another. The Rational brain (hippocampus) has no memory that can contextualize the sights, smells, sounds, and depraved experiences and say, “It’s ok, we have seen this before.” Dissociative reactions may happen for the first time even in these moments.

Even in the non-kinetic experiences, those previously-held subconscious beliefs about reality in the hippocampus are overwhelmed. The sight of children and animals living in unthinkable conditions. Handling body parts of the dead. “Anticipatory anxiety.” Immense guilt over what your mind later determines to be “avoidable” tragedies. Chronic fatigue. Indeed, war, in every sense, is a “violation of everything your mind thought was right.”12

Post-traumatic stress does not affect every individual exposed to these stressors. But regardless of the degree of training, intestinal fortitude, or mental toughness, a constellation of additional factors from childhood experiences to frequency to the introduction and timing of TBI can uniquely combine to have residual effects in any brain.

Extreme Stress Re-Wires the Brain

If the rational mind cannot comprehend a scenario, it shuts down. Our minds want desperately to compartmentalize and make sense of each experience. When the brain cannot contextualize extreme trauma, the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex experience neuronal cell death. Cells die.

Extreme stress is toxic to the brain. In chronic, severe PTSD and TBI, damage is physically manifested. Physical damage in neurons, degraded connectivity (white matter), “hypofunction,” and atrophy (shriveling) of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex have been observed and measured through tools such as, brain scans, functional neuroimaging, new variations on CT scans, high definition nerve fiber tracking, and single-voxel proton MR spectroscopy.

Not only have images shown withered hippocampus in these cases, but the brain studies have linked the increased size of the amygdala to PTSD severity. The primitive parts of your brain physically take over- in measurable ways. The higher the degree of atrophy, the more likely, frequent, and severe dissociative symptoms become in the individual positive for that subtype.

The severity of previously-believed “invisible” wounds can be observed, measured, and quantified through advanced brain imaging. This technology, as it pertains to PTSD and TBI imaging, is still developing and not in wide use. The military has dedicated large amounts of money to developing and testing these tools, but actual centers that provide adequate imaging and treatment are all still very new. Mere CT Scans or MRIs are simply unable to demonstrate the neuron-level damage involved in the brain with severe PTSD, TBI, and/or dissociative symptoms. Despite what we saw after Vietnam, despite Iraq and Afghanistan, we are still in relatively early stages of understanding, identification, and treatment.

Trauma is Cumulative Traumatic events are “cumulative.” The more you experience trauma, the more severe your brains physiological reaction to stress becomes, and the chemical composition changes.

Ok, so we know that in an extremely traumatic event, the Rational/Inhibition Circuit is overwhelmed by the extreme information it receives, and thus, fails to oppose (calm) the amygdala/”Activation circuit.” The amygdala then goes from zero to 100 on the activation scale, igniting the rest of the circuit. The CRF hormone is released, acting like a whip to a horse. Dopamine and Norepinephrine are those horses. The result is a mind acting on raw and irrational stimulus, not cognitive reasoning, and these moments of “hijack” can physically kill neurons.

But, is the balance then restored thereafter? Not exactly. When the mind dissociates during an extreme stressor, the amygdala records all subsequent experiences, feelings, and information for the duration of the dissociation, storing those sensations as life-threatening events without any associated contextualized, calming thoughts. Thus, those “memories” in the amygdala remain strongly in place as powerful unconscious future generators of panic or rage. From that time forward, unless properly treated, mitigated, and controlled, the amygdala is vulnerable to “triggers” that conjure those same images, feelings, and sensations from that experience. The later experiences do not have to even be the same subject-matter as the original trauma, just sensations that remind the amygdala of how it felt in that first dissociation. When that happens, “fear memories” in amygdala become triggered without conscious control and “fight or flight” can be engaged.

Since cells die and the amygdala grows with each amygdala hijack, it becomes increasingly easier for the switch between the two circuits to become “disregulated.” The veteran experiences “circuit modulation” at a more rapid rate. The hippocampus is shrinking. The amygdala is growing. The more he endures, the more the control center loses control or is compromised. If dissociative symptoms are present, the dissociative “disregulation” will be easier and more severe the next time, and the next.

Feedback Loop

The brain also becomes predisposed to the release of CRF, glucocorticoids, and adrenaline. It’s a vicious cycle known as the “feedback loop.” As instability increases, more trivial reminders serve to trigger the release of these chemicals that are toxic to the brain in excessive doses. And the more traumatic episodes that are triggered, the more the amygdala records new traumatic experiences, multiplying the scope of experiences that could potentially ultimately trigger a dissociation. A rough example would be a traumatized skunk that panics and sprays at any stimuli in its environment.

The brain’s intricate threat-response mechanisms erode to reflect a more primitive, animalistic system. For instance, the tiger or the mouse can tolerate very little stimuli before they instinctively enter “survival mode,” choosing either to attack or flee. Their circuit modulation is immediate. Their brains release adrenaline or dopamine in less sophisticated ways. The hippocampal memories and beliefs are not strong. The fish or the snake have even fewer working mechanisms, causing immediate, instinctive, and intense response to even minor perceived threats. There is very little “white matter.” The response is not malicious, hateful, or intentional. It’s simply the brain’s, albeit irrational, reaction to a perceived threat.

As time wears on, and the feedback loop repeats over and over, the structure of the Rational Circuit is wearing down, almost like a knee loses cartilage with prolonged stress, soon to be bone-on-bone if not mitigated.

Combat Veterans are not Ticking Time Bombs

As I said before, I want to note that, while these phenomena are important to understand when analyzing a case after-the-fact for intent and mental responsibility purposes, the described injuries to the PTSD suffering brain are not permanent. They do not mean that the sufferer is without hope of recovery. In the overwhelming majority of these cases, the criminal episode triggered by PTSD/TBI came at a time when the veteran was either (1) not properly diagnosed or treated (2) Not receiving proper treatment, trying to fight through the wounds, unwilling to admit there were problems due to a well-founded fear of social and professional stigma or (3) at a vulnerable time of transition between medications or treatment.

For all the criticism, the Department of Defense and VA are advancing in identification, diagnosis, and treatment. With such an incredible rate of veterans returning from multiple deployments, the stigma is being removed. Chronic, severe PTSD symptoms are identified, managed, and treated. Nevertheless, the identification and treatment gaps exist and incidents happen.

The “Perfect Storm”

Not every brain exposed to combat trauma endures the onset of PTSD symptoms. And not every PTSD subtype includes dissociation. And dissociative reactions are typically not severe, nor do they result in criminal activity. A constellation of circumstances is typically necessary to set the conditions for a dissociation that results in potentially criminal behavior.

Prosecutors may remark how “convenient” a lack of mental responsibility defense is after a severe dissociation resulting in a criminal incident. However, a post-mortem, reverse-chronological analysis should reveal signs and aggravators that were present in the days leading to the ultimate severe dissociation. We see less of a veteran setting up some self-serving alibi, and more of a patient overwhelmed to an extent previously not experienced. As the symptoms are escalating, the veteran may not be fully aware of the implication and severity.

The constellation of factors may show a recent immersion in reminders or triggers, such as seeing old war buddies. It may include a time of extensive dysmorphia, or increasing incidents of amygdala hijack, such as “individualized dissociations.” We may see changes in medication management and therapy. We may see another recent mild-severe TBI. We may see alcohol. Let me discuss some of these potential “perfect storm” factors below:

Individualized Dissociation

Varying degrees of dissociation exist on the spectrum leading up to a dissociative disorder or a major dissociative episode resulting in criminal behavior. A dissociative episode technically happens when you are driving while sleep-deprived, then “zone out,” unable to recall the last few miles. While this is not the pathological disruption in consciousness that results in unintentional criminal acts, it is a minor dissociative event.

Symptoms of dissociation may occur in the moments of a battle, never to be seen again or develop into a disorder. However, repeated trauma, re-experiencing, or repeated dissociative disruptions can develop into a “disorder” wherein dissociation becomes more common and more intense as the brain is physically changing with each experience. The road to an ultimate major “criminal” dissociation is often marked with smaller, individualized dissociative episodes. Veterans may experience moments where they seem to lose their sense of “self” (derealization/depersonalization) but were able to re-gain control quickly. In these individual moments, the mind becomes more and more susceptible to the triggers. These dissociative disruptions are quicksand.

By way of analogy, athletes know that once you have that first severe ankle sprain, the next one, and the next after that, will happen much easier. Another analogy would be the Chuck Palahniuk book/movie Fight Club. Early in the film, Ed Norton’s character would splice into “Tyler Durden” only momentarily. But as the events wore on, he would unknowingly splice into “Tyler Durden” more frequently, for longer periods, resulting in more acute behavior. While schizophrenia was the defect developing in that movie, the deleterious effects are similar here. One severe episode, one panic attack, one heat-related casualty, one severe dissociation will always make the next, and the next, easier and more severe.

The Marine or Soldier often has little understanding of their condition. They do not notice the erosion of their cognitive functions. But in increasingly-trivial ways, they will “disregulate” into “survival mode.”

Repeat Deployments

First, at no time in our nation’s history, have we re-deployed combat troops back and forth 4, 5, 6 times, as we do regularly today. Consider what we know about the cumulative and toxic effect of repeat trauma. Not only are veterans with PTSD experiencing repeat trauma within each deployment, but they are coming home to struggle with their reality, only to be launched back again. And again.

That’s not to say the deployments are involuntary. Ask a group of warfighters with PTSD if they would return in service of their country, and you will get a roomful of raised hands. I’ve had cases where Marines stopped taking medication or hid their PTSD symptoms, not fully understanding the potential consequences, specifically so they would be allowed to accompany their brothers back into the fight. However, the experience does not become any less traumatic. The neuronal cell death, the hippocampal atrophy, the feedback loop are simply normalized. It may take deployment two or three before the repeated trauma results in PTSD or dissociative symptoms, especially if even mild TBI is involved.

Traumatic Brain Injury

TBI brings a whole set of aggravators, deserving of its own separate discussion beyond the scope of this Article. In cases of severe dissociation resulting in criminal consequences, a TBI is overwhelmingly present. TBI alone can cause cognitive and psychiatric problems, rewiring the brain.

TBI alone damages neurons and kills cells in the hippocampus. The brain swells, and in cases of repeat TBI, even relatively minor impact, the swelling and inflammation in the cells brings much of the same physical damage, with the same effects described above. Even relatively minor repeat concussions can cause major brain damage. Look no further than the recent publicity of the effects of TBI on NFL players, months, years, and decades later.

Medication Complication- Another Marine’s 2013 Trial

Complications from medication prescription are often found in the “perfect storm” of aggravating factors behind a severe dissociative episode. “Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome” is used to describe the body’s reaction to an abrupt stoppage of antidepressant medication. Antidepressants are typically prescribed in the form of “selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors” (SSRIs). SSRIs are used to increase the serotonin supporting the Rational/Inhibition circuit. SSRIs rein in the CRF, dopamine, and adrenaline production. SSRIs have even been shown to rejuvenate neurons in the hippocampus. Lexipro is an example of widely-prescribed SSRI. Similarly, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), like Effexor, are also widely used to treat depression, anxiety, and panic attacks.

The medication artificially replicates what the system should be doing under healthy conditions. Antidepressants have had positive results in system regulation. However, when the SSRI/SNRIs artificially accomplishes this balance, the body stops forming those synapses. Thus, when medications are stopped too quickly, “cold turkey,” or switched incorrectly there’s a serious deficiency. Those receptors are not catching synapses like they should.

“Withdrawal” is often used, but it’s not really the proper term, because antidepressants are generally not habit-forming drugs that engender “drug-seeking” behavior. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome can first present even after several days of SSRI/SNRI use. It has been found to occur in 20% of patients who abruptly discontinued taking antidepressant they had been taking for at least 6 weeks. Discontinuation symptoms can happen as soon as hours after the first missed dose, but usually 3 days.

Numerous reasons exist for why an individual would stop taking medication. Antidepressants can cause drowsiness, an indifferent attitude, sexual side effects, and agitation that can have professional and social consequences. Like much of the larger society, combat PTSD vets do not want to be dependent upon medication. Or, given the serious cognitive and behavioral symptoms that come with severe PTSD/TBI, individuals can slip into a periods where they forget or do not want to take the meds. If not fully educated on the risks, individuals may stop taking the meds for a short period, trying to fight through symptoms, without a full appreciation of the potentially devastating consequences.

What do discontinuation symptoms look like? Cases have presented “psychosis, catatonia, severe cognitive impairment.” Antidepressants, even when taken properly, have shown a risk for “manic-like” reactions and loss of impulse control. The syndrome causes an individual to lose orientation to time and space, leaving the individual dissociated from their self and their surroundings. Case studies and peer-reviewed articles have been published in the American Journal of Psychiatry and elsewhere describing the neuropsychiatric effects of discontinuation of antidepressants like Effexor, for instance. In some cases, individuals with SSRI discontinuation syndrome may experience a brain shut down during complex and chaotic situations, and those persons may not be able to appreciate the nature of their actions.

Those symptoms should sound familiar by now. Talk about a perfect storm. The improper use or constant shuffling of antidepressants can independently serve to trigger the same “out of body” cognitive effects as a PTSD dissociative reaction.

Don’t Rush to Blame Alcohol Consumption

Sometimes this antidepressant discontinuation syndrome can look like drunkenness. In a 2013 case, I defended a senior enlisted Marine Purple Heart recipient who had an incident at a charity fundraiser in bar. He was charged with, among other things, drunken and disorderly conduct, criminal threats, and assault. Despite his apparent “drunken” stumbling, erratic behavior, and slurred speech, evidence showed that he had very little alcohol that night. He was receiving treatment for severe, chronic PTSD with mild TBI. His doctors had been experimenting different medications. All were causing insomnia and abnormal behavior. Two days before this incident, he had “cold turkey” discontinued the antidepressant Gabapentin (Neurontin), because it was causing him to be drowsy during the day while on duty.

The symptoms of Gabapentin discontinuation include disorientation, irritability, numbness of arms and legs causing balance issues, flushed skin, confusion, hallucinations, to name a few. The reactions may look like “disorderly” or violent behavior. Sound like alcohol intoxication? Gabapentine is not the only antidepressant that can mask as “ethanol withdrawal.” The oft-prescribed Ativan and Lexapro for example, can present some “drunken” symptoms. The same physiological pathway that is affected by booze is the system that is affected by neurontin or gabapentine.

TBI can also mimic alcohol intoxication. TBI has symptoms of mental confusion, dizziness, double vision, tired eyes, slurred speech, loss of coordination, numbness in extremities, confusion, vomiting, and dilated pupils. In severe or repeated TBI, the symptoms can persist years after the physical trauma.

Thus, while alcohol may serve to trigger, aggravate, or weaken the body system, in a case such as this, the overriding, substantial, and true cause of the impairment is the mental and physiological withdrawal the body suffers from the medication discontinuation and TBI.

That Marine was also justly acquitted of all charges. The incident served as a catalyst for better treatment and doctor-patient relationships. Instead of being discarded as a criminal in the “system,” the combat vet and his family are thriving and healthy today. Without experts and attorneys who could distinguish the facts and circumstances that showed why this was PTSD-related and not drunkenness or rage, the innocent man could have been pressured into accepting an unfavorable plea deal.

PTSD or no PTSD, Military members drink alcohol. Alcohol, while often present and even possibly on the breath of the dissociating veteran, is not necessarily the main catalyst in the criminal incident. Even if he exhibits signs of a “drunk,” when we are talking about severe PTSD, dissociation, and/or “cold turkey” med stoppage, alcohol may simply be just one aggravating factor in the constellation of aggravating factors, generally beyond the understanding of the accused. We must not let alcohol consumption (generally, not a full defense) be the copout explanation for the accused whose behavior and symptoms are more accurately the result of complications from medication and PTSD/TBI.

Legal Defenses at Trial

Whether your trial is a Court-Martial or in another criminal court, the potential PTSD/TBI-related defenses will fall into one of two main categories. 13 First, lack of mental responsibility (insanity) is a full defense to any criminal responsibility. Second, “partial” lack of mental responsibility is a defense that negates the mental requirement necessary for more serious crimes, reducing your potential guilt to less-serious offenses.

Let me talk first about the general requirements for these defenses, then discuss how they can be proven at trial.

The Affirmative “Lack of Mental Responsibility” Defense

The complete defense of lack of mental responsibility, or “insanity,” is judged at the time of the offense. I say “insanity,” but this can also be “unconsciousness” or a type of imperfect “self-defense.” This defense in the military, as it pertains to PTSD-related reactions, does not necessarily mean the veteran must be committed to a hospital or is presently a societal risk.

The military’s test for lack of mental responsibility is based upon the old English law M’Naghten test. 14 This full defense is called an “affirmative” defense. It requires the defense attorney to give pre-trial notice of the “insanity” defense.15 If the government is able to prove the actual acts of the underlying charged offenses beyond a reasonable doubt, this defense would then require the jury to vote whether the Defense proved by a “clear and convincing evidence” that, in the moments of the alleged incident, the veteran:

- Suffered from a Severe mental disease of defect,16 and was

- Unable to appreciate the nature and quality or wrongfulness of his actions at the time of the alleged actions

As for the first factor, severe, chronic PTSD, even without the “with dissociative symptoms” subtype is a “severe mental disease of defect.” DSM V “Axis I” diagnoses are generally considered to be severe defects, and could include chronic, severe PTSD, TBI, or even major depressive disorder. Typically, severe PTSD has been diagnosed and is being treated before the incident, but even a mental examination that reveals the presence of PTSD/TBI/Dissociative symptoms after the fact may be used to prove the existence of a disease or defect at the time.

The second factor must be proven though the facts, witnesses, and experts described below.

Defense teams that have successfully attempted and proven the second factor are shockingly rare in the military. But should they be this rare? Isn’t the inability to appreciate “nature,” “quality,” and “wrongfulness” of actions exactly what happens in the moments of the symptoms and reactions described in this article? Wouldn’t some of those dissociative reactions result in aggressive or “criminal” behavior? While severe PTSD is not a carte blanche excuse for intentional criminal behavior, I think a true understanding of the mental responsibility defenses and the science behind a dissociative episode would suggest that courts and defense attorneys are overlooking this critical defense in the military far too often.

Self-Defense. In addition to a dissociation that may result in affirmative criminal acts, the defense may also arise in self-defense situations. Say, a veteran with severe, chronic PTSD is assaulted in a bar, and a mix of factors and triggers place that individual into a dissociative state, igniting a conditioned, automated response. The dissociative reaction may result in pure amygdala aggression, disproportionate in force, resulting in criminal charges. While not a defense or excuse for every bar fight, this type of reaction certainly and expectedly occurs.

The same has been true when a troubled veteran, because of the effects of severe, chronic PTSD, erroneously believes that the victim is reaching for a gun to kill him. The scene, while not necessarily resembling Iraq or Afghanistan, can evoke triggers, mixed with kinetic observations, that could lead to the veteran’s genuine, but subjectively irrational, belief that his life was in imminent danger.

“Partial” Mental Responsibility Defense

The great majority of cases do not give rise to a complete “lack of mental responsibility” affirmative defense that can be proven by clear and convincing evidence. However, severe PTSD symptoms at the time of the offense may still, nevertheless, be relevant to show the veteran’s diminished mental capacity, negating the required state of mind at the time of “Specific Intent” crimes.

With respect to “Specific Intent” Crimes, the government has to prove that the defendant, beyond a reasonable doubt, was mentally capable of entertaining specific intent to commit specific acts, with a specific ultimate objective. General intent crimes, by contrast, simply require the proof that the defendant generally intended to perform some action that resulted in a criminal act. Whether the defendant intended the specific end result or not is less relevant for General Intent crimes. Specific Intent crimes include First Degree Murder, Larceny, Criminal Threats, certain types of Assault/Sexual Assault, Kidnapping, aggravated forms of Battery, to name a few. For instance, someone may jump in a car they don’t own and drive off without permission. That is the “act” of a theft. However, if the defendant, for whatever reason, did not formulate the intent to permanently deprive or steal the car when they got in and drove it, they are not guilty of the elements of “larceny.” 17

These allegations require the prosecutor to prove, not only that the accused intended to commit an act, but that the accused intended a specific end result with the act. The prosecutor must prove that intent “element” beyond a reasonable doubt. Therefore, the evidence the Defense team presents in this regard is not a separate “affirmative defense.” It is simply evidence that negates the elements that the prosecutor has to prove in the first place. Does the veteran’s condition in the moment raise a reasonable doubt as to whether he truly formulated the specific intent to commit an uncharacteristic crime? I submit that it does more often than it is recognized in criminal courts today.

Per the military jury instructions on the “partial” mental responsibility, the accused may be “sane” and yet, because of some underlying “condition,” “character or behavior disorder,” “deficiency,” “impairment,” or “defect” at the time, he was “mentally incapable” of actually consciously entertaining the specific intent required in the allegations. While these states are not a built-in excuse in every case involving a combat veteran with PTSD, these underlying conditions do emerge and certainly result in unintended criminal incidents in severe cases.

Keep in mind, even voluntary alcohol intoxication can serve to negate the “specific intent” element in criminal court. How much more compelling are the physiological effects described above? If alcohol causes uncharacteristic, unintended behavior, PTSD, if understood by the court and defense attorneys, certainly does to a much more compelling degree.

In presenting this type of evidence to the court, the Defense team is entitled to present their own mental health expert(s) and lay witnesses to the veteran’s PTSD and behavior, just as in the affirmative “lack of mental responsibility” defense. I will briefly discuss the sanity inquiry, procedural, and disclosure requirements that come with either of these defenses.

The Presentation of Evidence At Trial

The science may be clear. The fact that the individual could not form criminal intent or was dissociating at the time of the offense may be apparent. However, the Defense must still present the case accurately and coherently. Whether fair or unfair, the burden will be on the combat veteran to prove these defenses to a judge or jury that is often skeptical of or calloused to “psychobabble,” “malingering,” or “mental illness.” “Innocent until proven guilty” goes out the window when the Defense team alludes to these defenses in an opening statement. Vets do need the right experts and attorneys that can understand the complexity of the science involved and convey the truth in way that is credible and clear.

The servicemember, loved ones, and, likely, bystanders know that something went wrong that day, that he is not the criminal that a charge sheet now says he is. Legally, then, I will discuss what evidence is presented at trial to connect the condition to the allegations.

Medical Testimony

“Mental Responsibility” defenses will almost certainly require findings and testimony from qualified medical professionals that support your case. Both treating psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, psychologists, etc. and independent forensic experts should be used to (1) Establish an accurate diagnosis, and (2) Directly connect the phenomenon of the diagnosis to the alleged acts in the case.

While not necessarily required prior to the alleged criminal incident, the accused was likely already diagnosed with a chronic, severe form of PTSD. While a developed medical history will generally be important to the defense, this does not mean that one must have a litany of past documented dissociative episodes or an extensive treatment and prescription history. As discussed above, it often takes a criminal incident or severe dissociation to reveal expose the severity, need for a higher echelon of intensive treatment, or the need for altered treatment decisions.18

The defense attorney should recognize the need for an “inquiry into the mental capacity and responsibility” at the time of the offense early. In the military, this is an evaluation pursuant to Rules for Courts-Marital 706. If there is any cause whatsoever to doubt the mental capacity or responsibility, the mental examination must be granted by the court. 19

A proper military “706 Board” sanity evaluation will be the subject of its own separate future article. These boards can either be a great help or an incomplete, empty exercise. Here’s a very typical scenario: a military defense attorney requests the court to perform an evaluation of the accused at the time of the offense; court grants it, ordering the prosecutor to arrange it; Defense team sits back and waits for the results; prosecutor has the Army or Navy hospital pick from a rotation of mental health experts to evaluate him some morning, often double-stacked with an afternoon evaluation; prosecutor supplies a charge sheet and whatever records he or she deems “relevant;” a single person meets with the servicemember, runs two standard tests, and looks at the medical records all within the assigned 3 hour block; neither the treating physicians nor witnesses to the behavior are consulted in this 3 hour block (Navy hospitals guidelines require the entire exam and report all to be completed and submitted within the same 8-hour work shift); and by lunchtime, the troubled veteran is found to be perfectly fit at the time of the offense.

While these are overwhelmingly well-meaning medical professionals, they are given neither the time nor the information necessary to provide a thorough, reliable analysis. For instance, psychologists are assigned to evaluate cases that involve potential medication complications. Psychologists, while critical to psychotherapy and treatment analyses, are not medical doctors who prescribe or deal with medication management. Psychiatrists do that. However, the hospital may not even know what the case entails, because no one adequately informed them beforehand.

This is but one example of why a military defense attorney must get out ahead of the R.C.M. 706 Board. First the attorney must make sure that the order directing the Board is complete and explains all reasons why mental responsibility may be in doubt.20 The attorney also must compile and submit documents, prescription records, witness statements, and treating physician information that will help supplement and inform the examiner in their brief time window. The 706 examiner must itemize what information he or she relied upon in their conclusion. If they did not properly consider what the defense submitted, the findings are deficient. Defense counsel must also ensure proper time is given to the examiner. If the case involves severe PTSD symptoms, potential dissociation, and/or medication complications, significant research and evaluation is required. Of course, the evaluator will very likely testify that they could have used more evidence and more time than is currently provided in the current parameters of rather generic evaluations. If a new report would ensure accuracy, thoroughness, and prove helpful to the court or trier of fact, the attorney should move for a new Board.21

The 706 Board may very well be incomplete, insufficient, and may come back saying the accused was fully able to appreciate his actions at the time of the offense. However, that is not the end of the Defense. In the second above-mentioned 2013 court-martial involving PTSD and medication discontinuation, the 706 Board was a check-in-the-box, performed by a psychologist not trained in mediation effects, lasting from 0930-1230 some Wednesday. However, we sought, and were granted, an independent forensic expert who spent the appropriate time analyzing the Marine and the records. Her ultimate opinion was far more helpful to the jury, discrediting the 706 Board examiner, who fully conceded his lack of depth and expertise on the facts and circumstances in that particular case.

Forensic Experts

It’s critical that the Defense team obtains experts who understand the veteran and his condition. Even if the 706 Board comes back saying he could appreciate anything and everything, the judge must grant a forensic expert if the Defense can show cause to question the state at the time.22 Servicemembers have the right to present and establish defenses that are not frivolous,23 and, in the military case, they have the right to have the government pay for it.24 After the reversal of some convictions on these grounds in recent years, military courts have become generally fair and reasonable in this regard. 25

It takes a proper workup to provide a deep, reliable analysis of the factors and conditions in the case. The Defense will need dedicated, independent experts to assist in understanding all pre- and post-morbid personality diagnoses, the role of any medication, the subjective mental capacity, and how those issues fit into the Veteran’s neuropsychological profile. The Defense must understand how these factors interact and play a role in any mental responsibility defense. The expert must also consult with the Defense team on the extent that the Veteran’s present mental diseases and diagnoses affect him to this day, his risk level, and the type and extent of ongoing treatment necessary. This evidence is critical for any post-trial risk hearings or sentencing.

The expert will need time to review all medical records and raw data; conduct multiple interviews, not just a couple hours on one day; consider witness statements; conduct third party interviews; consult with treating clinical providers; conduct a battery of Psychological Testing Instruments to including the M-FAST (Miller Forensic Assessment of Symptoms), Personality Assessment Inventory, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality lnventory-2 (MMPI-2), TOMM, etc. In the case of suspected dissociation, tests could include the Dissociative Experiences Scale, the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory, the Traumatic Dissociation Scale, and the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire.

Multi-Disciplinary Analysis. Given the level multi-disciplinary expertise needed to properly analyze the facts and medical presentations, the case almost certainly requires more than one expert to meet the military requirements. Just as a singular “706 Board” examiner may not comprehensively provide adequate opinions, a single expert consultant will need to supplement other experts for a proper workup. For instance, additional neurological and neuropsychological testing or advanced imaging methods are often necessary. This requires separate examinations and tests to make comparative assessments of that frontal lobe executive functioning through time. A forensic psychologist may not be able to accomplish this or analyze the raw data properly without a neuropsychologist and/or neurologist. In another example, while a psychiatrist is preferable to the psychologist for the analysis of medication effect, a psychologist is the appropriate forensic analyst for the administration and interpretation of critical psychological instruments such as the MMPI, M-FAST, and TOMM.

Do Not Let the Government Pick the Defendant’s Expert. It should go without saying that the request for funding for an independent defense expert should not just be some generic request for any consultant to be chosen by the prosecution, as often happens in the court-martial setting. Each case presents unique challenges and critical aspects that require a particular expert with the relevant expertise in those aspects. Find that qualified person.

The government may try to supply a DOD-employed “adequate substitute.” But, to qualify as an “adequate substitute,” the person must be one with similar professional qualifications and who can testify to the same conclusions and opinions as the defense requested expert.26 A government expert whose views diverge from those of the defense expert is not an “adequate substitute.”27

Finally, while the veteran’s DOD treating providers will provide critical input and evidence -especially given the great number of Marines and soldiers they treat with PTSD today- the treating clinical providers should not also be the forensic experts in the case. The “Ethics Guidelines for the Practice of Forensic Psychiatry” discourages this practice, chiefly because of the inherent conflict of interest presented by a psychiatrist performing the dual functions of both clinical treatment and forensic evaluations for legal purposes. Indeed, it is often the treating provider’s treatment or misdiagnosis that is questioned to a degree in these uncommon cases.

Witness Testimony

In a trial involving these defenses, lay witnesses may also testify to their own observations of the veteran’s appearance, behavior, speech, and actions before, during, and after the incident. They may even give an opinion based upon what they saw, given the facts as they know them. That can be very relevant and powerful in the defense.

They will talk about how long they have known the veteran, how well they know him, his personality, his struggles, and his changes. The witnesses will talk about why what they saw was extraordinary or bizarre. The humanity of the “defendant” sitting at the table, branded by the charge sheet alone, is restored. Typically, this type of evidence is not admissible. People from the defendant’s life generally may not come in and talk about personality, relationships, or specific instances and observations.

But here, they have to. They have to explain and test the source and severity of the PTSD or Brain Injury. These are not tactics designed to pull on heart-strings. In a case where the existence and severity of mental defects are at issue, these observations are critically relevant.

The defense must include Marines and soldiers who fought alongside the accused. People who also lived the trauma “beyond the normal human experience.” Fellow warriors also likely saw the cognitive and behavioral changes (detachment, hypervigilence, risk-seeking behavior, etc) commence in country. When these cases present themselves, the veteran’s family, wife, and parents typically can go on for days recounting the behavioral changes with which they have lived. The memory loss. The erratic, confused behavior. The transformation that they never understood. The defense will also include witnesses from the alleged incident itself. While amygdala hijack or severe dissociation often looks less “zombie-like,” than just “autopilot,” the witnesses still will likely observe the prefaratory confusion, disjointed behavior, and bizarre responses described above.

It’s exactly why these cases are so excruciating: Loyal, kind, caring men of integrity are physiologically transformed by combat, finding themselves seated in a courtroom as a criminal defendant. But, through the presentation of this type of evidence, the defense is able to prove the severity of the transformation and the legitimacy of the symptoms. The jury can look into the eyes of friends and family members (who unfortunately are often also the victims), and hear them say, “That was not him that day, and here’s how I know.” It’s relevant. It helps the jury to understand where the real justice is to be found in the case. It must be presented effectively.

Herein lies the beauty of defending the American combat veteran. No matter what ugly allegations face the man, you know a hero resides within. The whole story not only humanizes the “defendant,” but it greatly benefits the jury to accept and understand the reality of the struggle.

Often, the jury members in the military are combat veterans themselves. It is natural for some of those members to be skeptical if they were not affected similarly. For this reason, again, it is important to clearly demonstrate the science that explains why, with a certain cocktail of experiences and factors, even the strongest warrior’s mind can be disrupted.

A Subsequent “Confession” does not equal “Guilty”

A subsequent “lucid confession” obtained by investigators in the hours after an incident does not necessarily mean that the veteran was not dissociating or otherwise lacking in mental responsibility in the moments of the incident. It is beyond the scope of this piece to launch into the general unreliability of police-induced “confessions,” the infamous “Reid Technique,” and the power of suggestion and coercion on a panicked mind.

However, I’ll reiterate that “lucid intervals” are not uncommon in these incidents. You catch glimpses as if out of the porthole of a ship you aren’t steering. It’s not a full picture or understanding of environment. It’s a prison. It leaves the “residue” of “emotional memory.”

The human brain craves control; wanting to reconcile things it doesn’t understand. When we have gaps in memory or lucidity, our brain strains to fill in the blanks. A symptomatic veteran may have “emotional memory” and flashes of recall that allows him to fill in blanks as he talks to cops or superiors in the aftermath. Memory encodes differently when prefrontal cortex is not “present.” The memories are not as much “cognitive memory,” as they are amygdala-recorded sensations. It’s more of a communicative memory than a narrative memory.

The subject knows they did something wrong, and servicemembers are certainly trained to accept responsibility for results without excuse. So while only the major “big ticket” facts and emotional memory is recalled with little detail, vague admissions are extracted by investigators. Unfortunately, the detail is usually suggested or wholesale filled in during the hours of interrogation.

Remember, even sleepwalkers know a fridge is a fridge when they unconsciously head to the kitchen at 0300. That mind on autopilot still knows the body is negotiating stairs. The part knows to put the club sandwich from fridge into the mouth and chew. The part of the mind controlling that scenario does not think that the stairs are marshmallows, or the fridge is a space ship. No, that part of the mind is interacting appropriately with the environment, even while the cognitive mind is absent.

Such can be the case with the severely dissociating combat veteran. A severe dissociation is not always a complete “flashback” to Hue City, Ramadi, or Helmand Province. The dissociating combat vet does not necessarily have to think that guy in bar or the helicopter overhead is Viet Cong or Taliban. The person does not have to think that he was battling Martians to be dissociating, unconscious, or lacking mental responsibility.

No, as demonstrated herein, when psychotic episodes happen, some interaction, recognition, and recollection of the surrounding environment is very possible and common. While a “confession” may very well be evidence of a knowing and voluntary criminal act, it certainly does not always “prove” that a dissociation or diminished state was not present at the time of the incident. A dissociating veteran’s recollection of sporadic glimpses outside the ship is not proof that he was steering the ship.

Post-Trial Risk Assessment

In the rare case where the Defense raises and successfully presents the affirmative “Lack of Mental Responsibility” Defense, the accused servicemember is not immediately released, as in the typical trial. Within 40 days of the “not guilty” verdict, that same court must hold a hearing.28 Again, this hearing is only appropriate in the case of the full lack of mental responsibility defense, not the diminished capacity or “partial mental responsibility” defenses.

At this hearing, the servicemember must prove that his release would not create a substantial risk of bodily injury or serious damage to property of another due to a present mental disease or defect.29 If the Defense cannot prove this, the military commander may commit the servicemember to the Attorney General, who turns the person over to a state or monitors the person until his release would not create a substantial risk of bodily injury or serious damage to another’s property.

Before this hearing, the medical experts will be called upon to, at a minimum, assess (1) The current severity of the accused’s mental disease or defect, and (2) whether due to this severe mental disease or defect the accused is a substantial risk of bodily injury to another person.

Only the current severity and risk level matters. As described above, the criminal incident usually serves as a catalyst to identify and ensure the proper treatment approach, medication management, and patient cooperation. It often takes a major event to get the type of interdisciplinary cooperation to solve this problem. It often takes a criminal event to wake that warrior up. To make the warrior accept he has a problem, to engage in treatment with whole heart, to undertand that he cannot fight this on his own.

Before the incident, the veteran likely was never identified to participate in an intensive resident treatment program like “OASIS” in San Diego, for instance. Intensive individual therapy, better support systems, cognitive behavioral therapy, service animals, the list goes on. Soon, the veteran, if he is not awaiting trial in confinement, learns to manage the symptoms, is able to sleep more, drink less, avoid certain activities or triggers, open up about experiences at the right times, make amends with self and others, and soon, the “criminal” incident becomes just another bad memory, the “bottom” that the servicemember had to hit en route to recovery.

In the first case described above, after the “Not Guilty due to Lack of Mental Responsibility” verdict, our Defense team had to essentially re-invent the wheel on military post-trial RCM 1102(a) proceedings. We could not find another case in the military where this type of verdict and required subsequent hearing process happened before in recent history. Our client had clearly changed his life and treatment approach after the incidents charged in the case. He was no longer a substantial risk. He had become a rockstar patient and a mentor to other struggling combat vets struggling with treatment. He was never turned over to the Attorney General, was returned to Wounded Warrior Battalion, and later retired honorably, happy, thriving, and incident-free.

Conclusion

While this article mostly involved the painful journey of the combat vet with PTSD, it should be clear by now just how tragically and profoundly PTSD and TBI affects the families and loved ones of these warriors. The families endure the pain of watching the transformation of their son, father, husband, or friend. They live through confusing ups and downs, only to eventually find themselves sitting in a courtroom behind the “defendant.” They are then often forced into the roles of “witness” or “victim,” still wondering what happened to the “real him.”

Even in the meritorious cases where these types of defenses are appropriate and successful, the verdict does not heal the wounds. What heals the wounds are proper treatment and awareness. PTSD is not some irreversible disease. Sufferers are not “broken.” PTSD itself does not make people violent. There’s hope. Advancement in diagnosis, technology, and treatment grows each month. Veteran support networks are flourishing. Combat vets, both with PTSD and without, are leaders in our society. The vast majority of combat veterans with PTSD never find themselves in a courtroom.

The trial defenses explored herein should not be presented lightly or frivolously. I’ve discussed narrow instances wherein the defenses presented themselves. However, when the factors for these defenses are there, justice demands that the combat veteran receive every zealous effort that his advocates can provide. It has become too easy to convict and punish the crime, without an understanding of the mind.

We must confront the physiological phenomena of PTSD/TBI, and that requires more than a “thank you for your service” before locking the cell door.

- Veterans Health Administration, Post-Deployment Health Group, Epidemiology Program, (2015), “Analysis of VA Health Care Utilization among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans”

- Id.

- Tanielian, T. & Jaycox, L. (Eds.). (2008). “Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Id.

- Steuwe, Lanius, and Frewen (2012). “The role of dissociation in civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for a dissociative subtype by latent class and confirmatory factor analysis,” Depression and Anxiety, 29, 689-700. Also, Wolf, Lunney, Miller, Resick, Friedman, and Schnurr (2012). “The Dissociative Subtype of PTSD: A Replication and Extension,” Depression and Anxiety, 29, 679-688. Wolf, Miller, Reardon, Ryabchenko, Castillo, and Freund (2012). “A Latent Class Analysis of Dissociation and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence for a Dissociative Subtype,” Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 698-705.

- Johnathan Shay (1991), “Learning about combat stress from Homer’s Iliad,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, October 1991, Volume 4, Issue 4, pp 561-579.

- Tony Horowitz (2015), “Did Civil War Soldiers Have PTSD?” Smithsonian Magazine.

- The Times, London, England, Tuesday, May 25, 1915, Page 25

- DSM-V, 300.14, Dissociative Identity Disorder

- DSM-V, Criterion B-3

- Dell (2001)

- Johnathan Shay (1994), Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character, Simon and Shuster

- Certainly, combat PTSD is always relevant in post-conviction mitigation and sentencing proceedings. In this article, I chiefly discuss the relevance of this evidence in your defense at trial on the merits.

- 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (1843)

- Generally governed by Rule for Courts-Martial 916(k) in the military

- A severe mental disease or defect does not include an abnormality manifested only by repeated criminal or otherwise antisocial conduct, or minor disorders such as nonpsychotic behavior disorders and personality defects. RCM 706(c)(2)(A).

- Psychiatric testimony or evidence that serves to negate a specific intent is admissible. Ellis v. Jacob, 26 M.J. 90 (C.M.A. 1988); United States v. Berri, 33 M.J. 337 (C.M.A. 1991); United States v. Mansfield, (C.M.A. 1993). The psychiatric evidence must still rise to the level of a “severe mental disease or defect.” UCMJ art. 50a.

- For example, different subtypes require different treatment approaches. Individuals with PTSD who exhibited symptoms of depersonalization and derealization tended to respond better to treatments that included cognitive restructuring and skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation in addition to exposure-based therapies. See, for example, Resick, Suvak, Johnides, Mitchell, and Iverson (2012). “The impact of dissociation on PTSD treatment with cognitive processing therapy,” Depression and Anxiety, 29, 718-730.

- A sanity board should be granted if it is not frivolous and is made in good faith. United States v. Nix, 36 C.M.R. 76, 80-81 (1965). “A low threshold is nonetheless a threshold which the proponent must cross.” The judge’s refusal to order a sanity board was not error where it appeared the motion for a sanity board was merely a frivolous attempt to get a trial delay. United States v. Pattin, 50 M.J. 637 (Army Ct. Crim. App. 1999).

- R.C.M. 706(c)(2) states, “When a mental examination is ordered under this rule, the order shall contain the reasons for doubting the mental capacity or mental responsibility, or both, of the accused or other reasons for requesting the examination.”

- R.C.M. 706(c)(4)

- “When the claim of insanity is not frivolous, to allow the court to determine that there is no cause to believe that an accused may be insane or otherwise mentally incompetent would be inconsistent with the legislative purpose to provide for the detection of mental disorders ‘not … readily apparent to the eye of the layman.” United States v. Nix, 36 CMR 76, 79 (CMA 1965).

- “Just as an accused has the right to confront the prosecution’s witnesses for the purpose of challenging their testimony, he has the right to present his own witnesses to establish a defense. This right is a fundamental element of due process of law.” United States v. McAllister, 64 M.J. 248, 249 (C.A.A.F. 2007). As a matter of military due process, servicemembers are entitled to expert assistance when necessary for an adequate defense. U.S. v. Garries, 22 M.J. 288 (C.M.A. 1986)